|

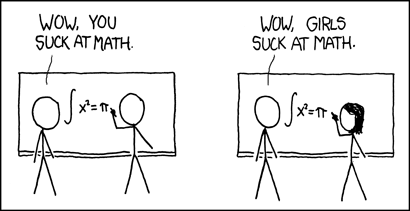

| "How it Works" from xkcd. |

So when we see girls underrepresented in a high level class in a given subject, what we have to blame is the messages we send to those girls that says "this subject isn't for you" or, worse, "you're at a disadvantage here." Those messages must be erased from our institutions if we want to have students who achieve great things. We need to destroy the institutional structures that hold students back in this fashion; these include stereotypes, teachers' attitudes, and some aspects of the tracking system. And even when we cannot outright eliminate the destructive structure, we need to encourage our young women to see those negative pressures for what they are and to excel despite them.

You'd think that in a progressive school environment filled with varied examples of strong intellectuals, you would no longer overhear statements that tie a student's performance to his or her gender. And it's true that I can't remember the last time I've overheard anybody speculate that a girl wouldn't be as good as a boy in a math or science environment, despite the fact that the stereotype persists in the world at large.

Stereotype threat is real, and it's one of the greatest barriers to student progress, particularly to the progress of struggling students. Whether the threat comes from a student's gender, race, or level assignment, it pervades every aspect of the learning process. It pushes a student to disengage from the daily work that builds mastery. It turns a failure into evidence of the stereotype and a success into a fluke. It demotivates, disheartens, and delegitimizes our students and their work.

Individual students struggle with maturity, abstract thinking, and complex systems, but generalizing those difficulties to a gender—or any group—is worse than useless. It's wrong; it limits our students; and we need to stop doing it. We need to be prepared for our individual students to have difficulties, but we should not expect them to have a difficulty because of their gender, and we should not excuse that difficulty as a result of gender.

And once we have erased it from our own assumptions as teachers, we need to go on the attack to shine the light of day on institutional and societal practices that create and confirm these stereotypes. Is leveling students so beneficial that we're OK with creating groups of students that we institutionally identify as less capable? Even knowing that by doing so, we're creating a downward pressure on their learning? Do we offer enough extra services to our "B-level" and "C-level" students to counteract our labeling of them as such?

I'm not sure that we do, and I wonder that if we changed some of our teaching models (large classes, teacher-focused learning, etc.), we might be able to reduce some of the need to track students and thus reduce the negative pressure.